Explore how John Locke’s philosophy shaped the concept of due process of law, connecting natural rights, reason, and constitutional liberty in modern justice.

1. Introduction

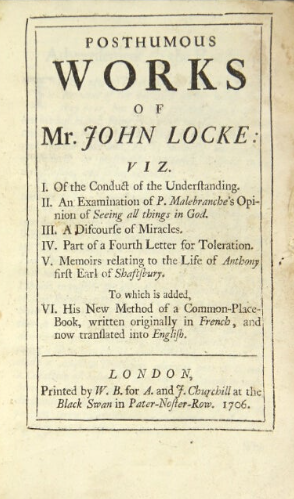

The phrase due process of law represents one of the most enduring foundations of constitutional democracy. It expresses the idea that no person should be deprived of life, liberty, or property without fair and rational legal procedures. Although its textual origin lies in the Magna Carta of 1215, its deeper philosophical roots reach into the political thought of the seventeenth century. Among the thinkers who defined modern liberty, John Locke stands out as the most influential. His vision of natural rights, social contract, and legitimate governance provided the intellectual framework that later became the moral and legal foundation for due process.

Locke’s ideas did not emerge in a vacuum. They responded to political oppression, religious conflict, and arbitrary rule that characterized Stuart England. By grounding political authority in consent rather than divine right, Locke offered a rational justification for resistance to tyranny. His philosophical arguments helped transform a medieval concept of procedural fairness into a moral principle of government under law. The goal of this article is to explore how Locke’s thought shaped the evolution of due process and how his legacy continues to define the relationship between the individual and the state.

2. Historical Context: From Magna Carta to Enlightenment

To understand Locke’s contribution, one must first consider the early history of due process. The Magna Carta’s Article 39 declared that “no free man shall be imprisoned or stripped of his rights except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” This phrase—law of the land—was later interpreted by English jurists as due process of law. Over centuries, courts and commentators expanded its meaning beyond procedure to include limits on governmental power.

By the seventeenth century, however, the Stuart monarchs repeatedly violated these protections. The arbitrary arrests, forced loans, and suppression of political dissent led to a profound crisis of legitimacy. It was within this atmosphere that Locke wrote his Two Treatises of Government. His philosophy responded directly to the abuses of absolute monarchy and defended the idea that government must act within the limits of law, reason, and consent. The transformation from medieval privilege to universal right required philosophical justification, and Locke provided it through his theory of natural law.

3. Locke’s Concept of Natural Rights

Locke’s central claim was that every human being possesses inherent rights by virtue of being rational and moral. In the Second Treatise, he wrote that in the state of nature, people are “free, equal, and independent,” bound only by the law of nature, which teaches that “no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.” These rights to life, liberty, and property were not gifts from rulers but moral facts grounded in human nature and reason.

This moral foundation transformed the meaning of law itself. If law is the expression of reason applied to human coexistence, then arbitrary power contradicts its essence. Consequently, due process is not merely a procedural device but a moral demand that the exercise of public authority respect the rational equality of all individuals. When a government acts without justification or fairness, it violates the natural law and therefore forfeits its legitimacy. Locke thus provided the ethical basis for later constitutional doctrines that limit state action and guarantee fairness.

4. Consent and the Social Contract

Locke’s theory of consent further developed the idea of legitimate legal order. Individuals, he argued, leave the state of nature not because they lose their freedom, but because they seek a more secure way to protect it. By forming a political society, they agree to be governed by laws that express the collective will, not the arbitrary will of a ruler.

This voluntary compact established the government’s duty to protect natural rights. It also introduced the notion that laws must be general, known, and applied equally. In Locke’s words, “Wherever law ends, tyranny begins.” This statement encapsulates the heart of due process: the law must rule, not the man. When rulers act outside the law, they betray the trust of the governed. Thus, due process becomes the procedural expression of political consent. Every legitimate act of authority must trace back to the agreement of those who are bound by it.

The social contract, therefore, not only founded political authority but also set the moral boundary that separates justice from oppression. Due process is that boundary in action—it transforms the abstract idea of consent into the practical requirement of fair and lawful procedure.

5. Property and the Protection of Rights

Locke’s notion of property occupies a central place in the genealogy of due process. He defined property broadly to include life, liberty, and estate. Since these goods represent extensions of one’s labor and personality, their protection is the main reason for forming government. Without secure property, freedom cannot exist.

In his time, property disputes often revealed the tension between royal prerogative and individual rights. Locke insisted that government cannot take or destroy property without the owner’s consent. This idea anticipated later constitutional clauses that forbid deprivation of property without due process. The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—“nor shall any person be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law”—echoes Locke’s philosophy almost word for word.

By grounding property in labor and reason, Locke linked economic activity with moral autonomy. Consequently, due process came to mean not only procedural fairness in courts but also lawful restraint on governmental interference with personal and economic freedom. It became a shield against both judicial arbitrariness and legislative overreach.

6. Reason as the Measure of Law

For Locke, reason was not merely an intellectual faculty; it was the standard by which laws could be judged as just or unjust. He rejected the notion that authority alone makes law valid. Instead, a legitimate law must align with reason, which itself reflects the divine order. Arbitrary decrees, even if enacted through formal procedure, violate this rational standard.

This rationalist perspective reshaped the moral meaning of due process. If the essence of law is rationality, then any process that ignores reason fails the test of justice. Consequently, procedural fairness must always be accompanied by substantive rationality. Later jurists would distinguish between procedural due process—the right to fair procedures—and substantive due process—the protection of fundamental rights against unreasonable laws. Locke’s philosophy provided the foundation for both dimensions.

Moreover, his emphasis on education and reasoned discourse implied that citizens must understand the laws that govern them. Ignorance and opacity are incompatible with liberty. Transparency, public deliberation, and accessibility of justice are all modern expressions of Locke’s demand that reason guide law.

7. Resistance and the Right to Revolution

Locke did not stop at theoretical limits on power. He also defended the right of people to resist or overthrow a government that violates the social contract. This idea linked moral duty with political action. When rulers act without due process, they dissolve the very bond that gives them authority. The people then return to the state of nature and may establish a new government that respects their rights.

This principle of justified resistance later inspired constitutional mechanisms such as checks and balances, judicial review, and the rule of law. Due process became the preventive form of revolution—a peaceful method to ensure accountability and prevent abuse. Instead of waiting for rebellion, societies built systems of appeal, fair trial, and independent courts. Locke’s radical claim thus transformed into institutional design: courts became the guardians of consent and reason.

8. Influence on Modern Constitutionalism

The intellectual legacy of Locke’s due process philosophy is immense. His ideas directly influenced the American Founders, especially Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton. The Declaration of Independence echoes Locke’s triad of life, liberty, and property—modified into “pursuit of happiness.” The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments constitutionalized the principle that no one shall be deprived of those rights without due process of law.

Locke’s influence also reached civil law traditions through the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Concepts such as legality, equality before the law, and protection against arbitrary detention all trace back to his vision of rational and consensual government. Even international human rights instruments, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, reflect the Lockean structure of inherent dignity and procedural protection.

Nevertheless, his legacy remains contested. Critics argue that Locke’s focus on property favored the propertied classes and justified social inequality. Others reply that his universal definition of rights transcends class distinctions and laid the groundwork for modern human rights. Regardless of interpretation, his contribution to the moral architecture of due process is undeniable.

9. Due Process as a Moral Language

Due process functions not only as a legal rule but also as a moral language of political legitimacy. Locke’s philosophy explains why. The demand for fair treatment, reasoned decisions, and transparent authority arises from our shared sense of justice. In every culture that values freedom, the idea that government must follow law resonates with Locke’s insight that political power exists for the preservation, not destruction, of rights.

In the modern world, due process governs far more than criminal trials. It shapes administrative procedures, immigration hearings, digital privacy, and even algorithmic decision-making. Each of these areas reflects Locke’s core belief: individuals cannot be treated as objects of power but as subjects of reason and consent. As technology evolves, the Lockean ideal of rational law must evolve too, ensuring that fairness and transparency remain at the heart of governance.

Thus, the enduring strength of due process lies in its philosophical depth. It connects the moral intuition of justice with institutional mechanisms that make freedom real. Through Locke’s lens, the rule of law becomes not a mere technicality but a moral covenant between governors and governed.

10. Challenges and Contemporary Relevance

Although Locke’s theory remains foundational, it faces modern challenges. Globalization, digital surveillance, and artificial intelligence test the limits of traditional legal guarantees. When algorithms make decisions about welfare, credit, or criminal risk, individuals often lack the chance to understand or contest those judgments. In such contexts, the Lockean demand for reason and consent becomes a call for algorithmic transparency and human oversight.

Moreover, the growth of administrative states raises questions about whether bureaucratic efficiency can coexist with procedural fairness. Locke would likely insist that the convenience of rulers can never outweigh the rights of citizens. His framework invites continuous reflection on the moral duties of power in any era.

At the same time, Locke’s emphasis on property has new implications in an age of data capitalism. If personal information represents a form of property, then its collection and use without consent may violate modern due process. The philosophical challenge is to reinterpret Locke’s principles for a world where liberty and property take digital forms.

11. Conclusion

John Locke’s philosophy remains the invisible architecture beneath the edifice of due process of law. He transformed a medieval procedural safeguard into a moral principle of government legitimacy. Through his theories of natural rights, consent, property, reason, and resistance, he gave due process its enduring moral force.

The world continues to change, but the Lockean insight endures: legitimate power must respect rational equality, and justice requires that authority answer to reason and consent. Every modern constitution that guarantees fair procedure or limits arbitrary power carries Locke’s intellectual signature. His thought reminds us that due process is not merely a legal formula; it is the living expression of moral respect among free and equal persons.

The philosophical roots that Locke planted in the seventeenth century still nourish the global tree of constitutional liberty. As long as societies strive to reconcile authority with freedom, the idea of due process—anchored in Locke’s vision—will remain the conscience of the law.